Experiments with AI Imagery’s Potential for Blind Users

Artificial Intelligence may help blind people use visual rhetoric in unexpected ways

Artificial Intelligence systems that have been trained to navigate meaningful connections between billions of reference texts and images are able to synthesize users’ text prompts into new images, extremely quickly and at very low cost. With a simple phrase like “Photograph of hands touching a bronze sculpture” AI text-to-image tools can nearly instantaneously generate realistic, attractive, and novel visuals. When almost everyone can make eye-catching custom images on demand, the question of whose images are worth paying attention to and what they are saying with them will become more important.

In my work designing and fabricating universal access exhibits, artwork replicas, and wayfinding tools intended for hands-on exploration, I’m frequently involved in preparing and conveying non-visual information to blind audiences. Naturally, I’ve wondered if AI image synthesis can be used the other way around; can blind people use AI text-to-image tools to communicate visual meaning to sighted audiences?

Unable to directly evaluate or vouch for the visual properties or fidelity of the images they may make, can blind users rely on AI-generated imagery to communicate anything meaningful or valuable at all, and where would that meaning come from?

In fall 2022, I asked my colleagues Brandon Biggs, Joshua Miele, and Lindsay Yazzolino, who are blind, if they were interested in experimenting with these questions. The three researchers—all experts in accessible technology design—wrote descriptions of a variety of subjects, from wayfinding to household objects, infographics and design, pop culture, and more personal, creative writing. I processed their writing in the Midjourney AI text-to-image generation system to produce thousands of new images, with mixed and fascinating results.

The images relating to animals and iconic works of visual art demonstrate our collaboration’s inherent and historic challenges, and the tool’s capabilities and limitations. They also hint at the intriguing prospect of blind users authoring images and seizing the attention of sighted audiences with compelling visual rhetoric in ways that have never before been possible.

ILLUSTRATING AN ANCIENT PARABLE

Brandon Biggs is a researcher, engineer, and PhD candidate in Human Centered Computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and he’s blind. The images below were generated from his description of an animal that he intentionally did not identify: “a large 4-legged animal with a long trunk, large ears, long tusks, hairless hide, and heavy.”

By design, the project participants described many of their subjects without directly naming them. That’s because simply telling Midjourney to generate an image of “an elephant,” for example, would let it jump straight to familiar elephant imagery, instead of testing its ability to construct images from the users’ unique texts. By leaving our subjects unnamed, we brought Midjourney into the ancient Buddhist parable about blind people’s competing perceptions of an elephant. We tested the AI’s ability to construct coherent visual representations from new, different, nonvisual perspectives.

In response, Midjourney gave us images of strange, animal-like assemblages with elephantine features, made of wooden or leathery, desiccated materials, as well as fairly lifelike renderings of a wildebeest-like animal, and immediately recognizable elephants.

Joshua Miele, Distinguished Fellow of Disability, Accessibility, and Design at UC Berkeley's Othering and Belonging Institute, is a research scientist specializing in adaptive technology design, and he’s also blind. He wrote a description of an animal most people know only from sight:

“A mammalian quadruped with a tawny hide and black spots, a short broomlike tail, and a very tall neck topped by a surprisingly small, almost chihuahua-like head sporting a turned-up nose, no ears, and two short vertical horns tipped with black knobs.”

Biggs described the same animal, but more succinctly: “Tall 4-legged animal with a very long neck, pointy ears, spots, and hooves.”

Denied a straightforward text cue like “a giraffe,” Midjourney did its best to construct creatures from these descriptions. Some of the results are bizarre and otherworldly, but in their strangeness, a few of the images evoke 17th-century European naturalists’ illustrations, or medieval illuminators’ depictions of implausible unseen exotic animals rendered only from second- and third-hand accounts. Some even seem to include parchment background textures and inked writing. They’re reminders that the challenges of generating imagery from language are very, very old—even older than text itself.

There are challenges in the other direction, too. Biggs’ and Miele’s text descriptions themselves—mentioning long necks and spots—echo longstanding linguistic limitations for describing visual novelty. From antiquity through the 17th century the animal in question had been known to many Westerners by a simple amalgam of names of more familiar beasts: Camelopard, from the Greek Kamilopárdali, for camel + panther or leopard. As in that name, individual elements of Miele and Biggs’ descriptions are recognizable to sighted viewers in all their images, even in the compositions that bear little visual resemblance to giraffes.

There’s no limit to how many competing visual interpretations can be generated even from a snippet of writing that succinctly highlights just a few prominent features, so it seems miraculous that Midjourney can even come close to accurately representing any description at all. Yet several of Biggs’ giraffe images were dead ringers. He had some luck, and a big advantage over medieval monks: AI text-to-image synthesis is like movable type for visual rhetoric. Biggs’ simpler description was apparently just enough to lead Midjourney to the statistical, semantic intersection of his text and the AI’s “giraffe-like” regions of billions of reference images, and to select appropriate visual type sets.

How precise do blind users’ written descriptions need to be for them to be able to lay their hands on big thematic chunks of visual rhetoric to make meaningful connections to visual culture that sighted people might recognize or respond to? And if we’re going to venture into deeply subjective territory, how should we go about evaluating the results, what benchmarks can we use, and what might the failures and limitations tell us? What do the images mean?

DECODING AND RECODING CULTURAL HERITAGE

Lindsay Yazzolino is a tactile technology specialist and researcher who is blind. She designs wayfinding and tactile communication tools. She and Biggs both described several famous works of visual art, an unusual and challenging proposition for more than just the obvious reasons. “Sighted people’s implicit exposure and references to the visual arts, and their allusions to their content and meaning usually leave blind people out of the discourse on these subjects,” Biggs explains.

Giving Midjourney descriptions of artworks that are not identified by name—and that are taken for granted and rarely explained in detail by sighted people—not only tests the AI by constraining it to the authors’ specific descriptions, but also allows blind users to illustrate their own nonvisual understanding of works which they know only from sighted people’s descriptions. Images created this way might also serve as engaging visual feedback to sighted creators about how well they are communicating with the nonvisual public about important works.

Biggs’ and Yazzolino’s AI-generated images may “fail” in some sense to closely resemble, visually, the original works they’re referring to, but using subjects that are only familiar to sighted audiences—and loaded with visually coded meaning—might give us a sense for Midjourney’s potential for widening the discourse, to connect blind users’ language to relevant visual artifacts, and to stir meaningful resonances between the authors’ texts, their themes, and their sighted audiences in a way that perhaps only imagery can.

Interpreting those resonances may be inherently unscientific, but taking the images' impact seriously and placing them in historical and cultural context are important parts of assessing these tools’ potential for communication.

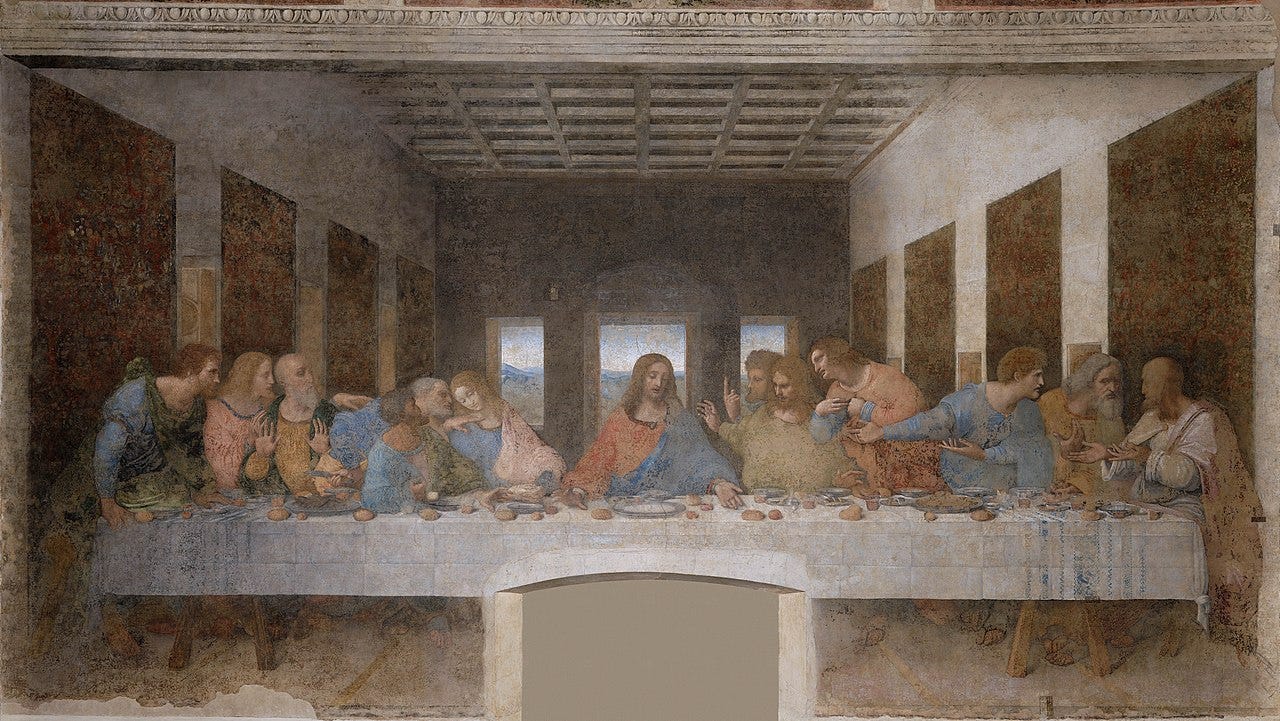

Illustrating Biggs’ point about exposure and discourse, he described Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, and included a detail he knows from the Bible that is not actually depicted in Leonardo’s work: “A painting of Jesus washing the feet of one of his disciples, while the others sit around a table eating dinner.”

The resulting images’ styles range from primitive, to surreal, to kitschy, but they each convey intimate, somber gatherings. And, undirected, in a seeming nod to Leonardo, in one of the images Midjourney has arranged the subjects and their table around a central vanishing point—a construction it dramatically overturned in Yazzolino’s images of the same scene. She described Leonardo’s painting, which she knows only from others’ descriptions, as a “famous painting depicting Jesus with his followers during the night before he is put on the cross.”

Like Leonardo’s composition, several images generated from Yazzolino’s description accommodate the viewer by arranging Jesus and his disciples opposite us, facing us, with Jesus in the center. But some do much more. In one version, with a cross marked in ash on his forehead, Jesus looks directly outward at us through bloodied, wounded eyes.

Where Leonardo demonstrated mastery of then-innovative one point linear perspective, with his architecture and environment receding into the distance, the depth in this new image has been flattened, as though seen through a telephoto lens. In an iconic Byzantine hierarchy, Jesus is depicted much larger than his disciples, looming over them.

This composition’s vanishing point and spatial scale have not only completely been inverted, but Midjourney has apparently synthesized one specific element of Yazzolino’s description—“a famous painting”—into a stunning, decisively 21st-century perspective. Seeming to recognize that images of “famous” paintings often have crowds of visitors in their foregrounds, Midjourney has rendered along the bottom of this composition the darkened backs of the heads of people who are themselves viewing the painting with us; we are in the crowded room with them, looking over and past them. They are roughly the same size as the disciples, and within their reach. One disciple, the third to the left of Jesus—where Judas is positioned in Leonardo’s depiction—looks away, while another looks downward, directly at the depicted viewers.

These shadowy viewers are motion-blurred, as though photographed in a long, low-light exposure, backlit by their own lights, which they are holding up to the painting—what appear to be mobile phones they are using to make their own images of the painting within the image. The yellow light they are casting onto the painting is rendered as the light within the painting itself.

Yazzolino’s synthetic image succeeds Leonardo’s by not merely accommodating its viewers, but incorporating them, their physical presence, their illumination, their act of viewing and memorializing, and us along with them, into the painting we are looking at together. This communal perspective is a startling way to convey intimacy and is an entirely new form of depth.

Yazzolino points out that in her own work helping designers and curators communicate visual information to blind audiences, “it sometimes seems like even sighted people have a lot of difficulty identifying and explaining in words what’s important in visual artwork.” And that is just the image itself. Beyond that, it’s impossible to identify all the tacit knowledge sighted viewers bring with them to a viewing to inform or motivate their responses. Subtle allusions, vaguely familiar gestures, misremembered colors or myths, and all-important context can move a sighted audience to recognize meaning in an image—or to generate meaning for themselves without knowing the difference.

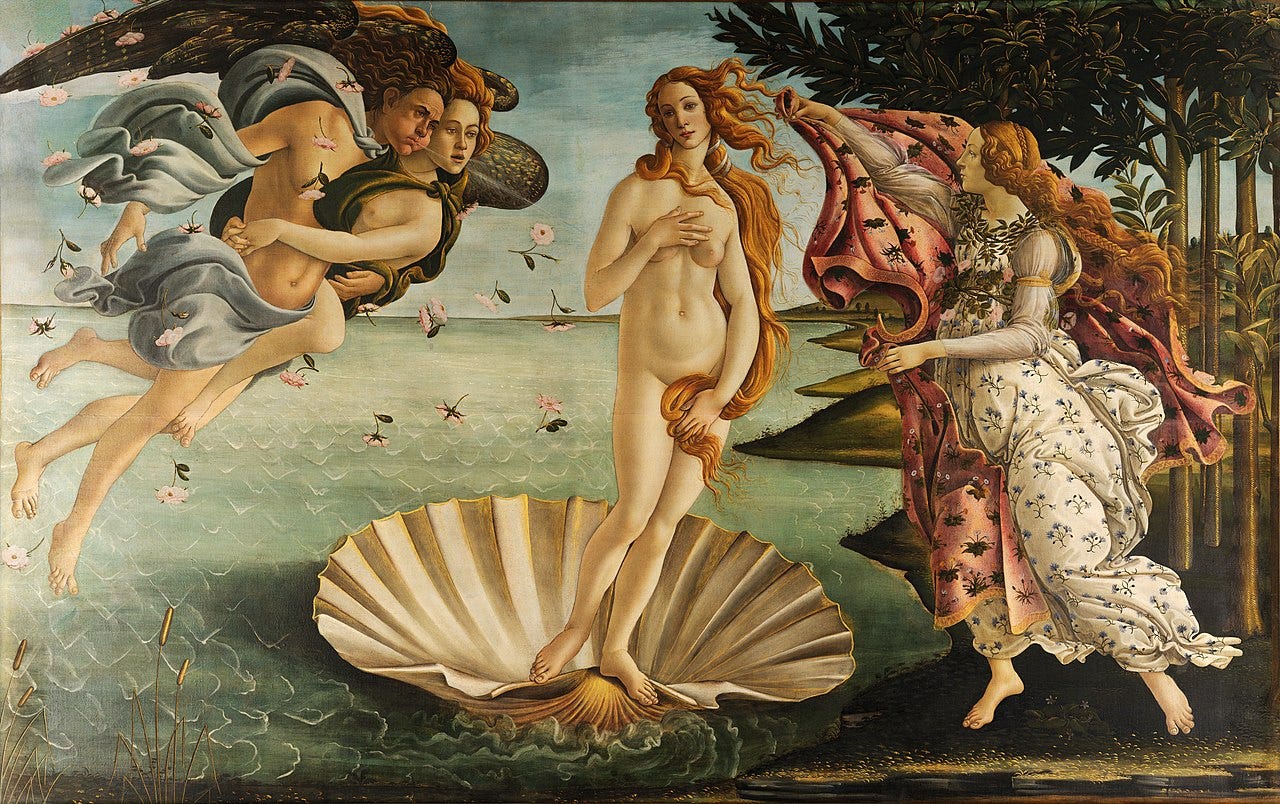

Even if their blind authors can’t directly vouch for what sighted people see in their AI-generated images, there’s certainly meaning to be found if we’re open to it—though we can’t be entirely sure from where or when it comes. For example, Midjourney’s renderings of Yazzolino’s description of Sandro Botticelli’s 15th-century The Birth of Venus—“a famous painting of a Goddess represented by the second planet in the Solar System''—hint at the Midjourney AI’s ability to mine a deep visual catalog of common culture to create figures, faces, and stylings that evoke ancient and classical deities.

Yazzolino didn’t mention the name “Venus,” of course, but two of her images present a woman in a forward-facing pose, her hands raised up to either side, similar to Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of love, beauty, fertility, and war—associated with the planet Venus—who holds up devices symbolizing her divinity in the 3,800 year-old Burney Relief.

Another of her images shows a female figure, without arms, standing, draped with flowing fabric that hangs from her hips, like the Venus de Milo, set against a marbled planet backdrop. Another depicts a more life-like female figure, her arms intact, holding a planet, with Venus de Milo’s face.

Biggs wrote two descriptions of the same Botticelli, producing wildly different mythic visions. His first: “A woman with wings flying over the ocean, with a wind god on either side. The wind gods are human in shape with wings.”

Biggs’ emphasis on wind and wingedness may have steered Midjourney to produce imagery more informed by the ancient Greek sculpture of the goddess Nike, Winged Victory of Samothrace with wings and windswept fabric alighting on a warship’s prow than by Venus or any Renaissance painting.

In his second description, Biggs included himself exploring a hypothetical tactile model of the Botticelli:

“I move my hands over the 3D rendering of this painting. On the right side, I feel a face, human head, and humanoid body with wings extending to the left of the painting. Below the feet of this creature are waves of water. As I move my hands to the right, I feel another human body of a woman emerging from the water in the center of the painting. To the right is another humanoid creature with wings facing the right side of the painting. Both of the creatures on the edges of the painting are watching the woman in the center as she emerges from the water.”

Midjourney doesn’t appear to have made a single, coherent whole from Biggs’ specific stage direction, instead blending the observer with his object into vivid, fantastical compositions and fiery symmetries that evoke William Blake’s mystical religious paintings more than Botticelli’s.

In all cases the participants’ texts—not their images—are the definitive expressions of their understanding of the subjects, or at least what they chose to share with us about them. Yet the visual traces of the famous original works that are sometimes found in the synthesized images can be striking, and confounding, especially with how hit-and-miss Midjourney can be with spare descriptions.

For example, Yazzolino described Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night as a “famous painting depicting a celestial scene of darkness.” Aside from their theme, as interesting, moody, and appealing as the resulting images are, without his vibrant brushstrokes, they bear little visual similarity to Van Gogh’s work.

Yet prompted by Biggs’ equally concise description of Michelangelo’s David, “A large marble statue of a muscular man, holding a sling,” Midjourney generated images of unfinished sculptures in chunky, rough-hewn stone, and hyper-detailed musculature that instantly evoke the determined, at-the-ready pose of the Renaissance masterpiece.

Biggs’ description of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa invoked indeterminacy—“A small painting of a woman behind layers of glass in an art gallery, with an unknowable expression on her face”—with mixed results.

His “behind glass” cue is rendered in several images as a reflection streaking across simple, loosely painted portraits. In others, Midjourney produced a more dramatic, cinematic feeling, with more dynamic compositions and complex reflections and distortions in the glass, over more-realistic-but-not-quite-life-like faces. Their expressions range from blank, to subtle smiles, focused, and worried. The images differ from each other as much as they do from the original artwork, and without any context, none are immediately recognizable as referencing the Mona Lisa.

VISUALIZING SEMANTICS AND GRASPING DEEPER CONNECTIONS

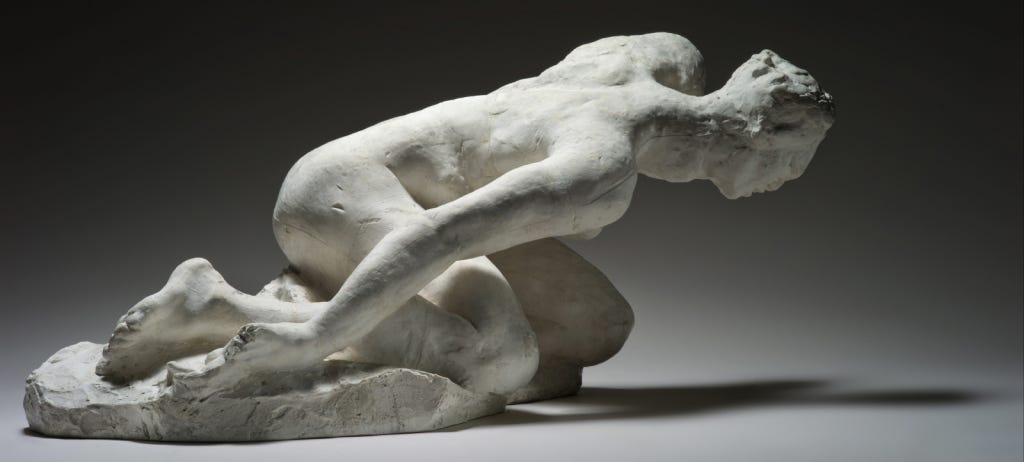

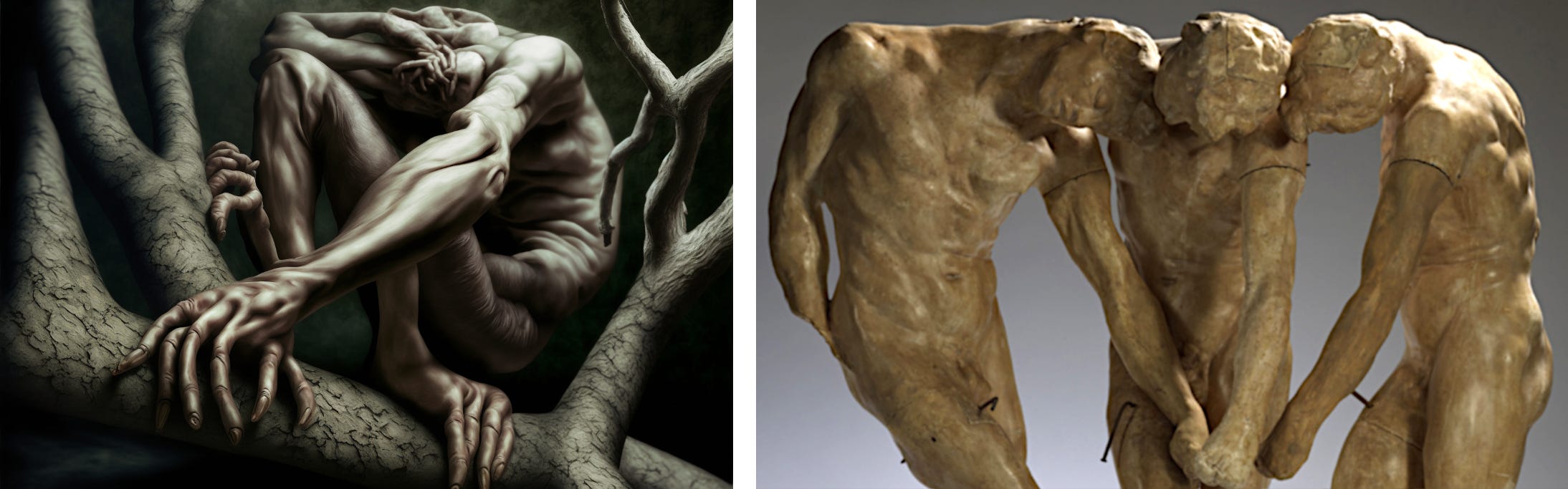

While organizing the project’s results, I’d originally thought to use several of the next set of images as dramatic examples of misfires—or maybe to not show them at all. Miele had described a sculpture of his own design intended to convey his sense of the style of works by sculptor Auguste Rodin. It was a subject I had suggested, and it turned out that Miele knows a few examples first hand from having touched them. Miele wrote:

“Thick limbs and stubby fingers, short men and twisted, interlocking partially embedded baby body parts, straining and struggling despite inevitable frustration and failure with infernal forces held back against barely better odds.”

I don’t know which of Rodin’s sculptures Miele might have touched. Many of his most well-known works are anodyne by modern standards—The Thinker and The Kiss, for example—and Miele’s text definitely does not evoke those. But I first thought of these results as failures mostly because I doubted that Miele had intended to create viscerally unpleasant images. When we reviewed his results by phone, I told him many were disturbing, and suggested “baby body parts” seems like a heavy text cue.

However, I do recognize in Miele’s text the recurring theme of unconventionally articulated, agonized anatomy in many of Rodin’s less accessible works. Since Miele knows some of Rodin’s works directly, through touch, he wasn’t limited to reprocessing other people’s visual descriptions. And unlike Biggs’ and Yazzolino’s earlier descriptions of famous artwork, Miele’s subject wasn’t a specific work, but a style, which he described too poetically to be dissected with any precision. So it should be no surprise if the images generated from his texts don’t look like Rodin sculptures.

Still, the more I look at them, the more I see how Miele’s images relate to Rodin’s sculptures. Their crowded, fused, and misshapen embryonic nodes shadow Rodin’s distorted silhouettes of menacing, hyperextended hands with painfully cramped fingers of plaster.

Miele’s goriest images share something in common with Rodin’s inventory of severed plaster body parts, which the sculptor referred to as abattis (giblets)—discrete, exaggerated anatomical expressions adapted from Renaissance and ancient Greek works, ready to be recycled, repurposed, and swapped from one torso to the next to quickly iterate new works on a modern, industrial scale.

Rodin’s exploration of the expressivity of irregular, oddly posed, and loosely modeled hands seems simpatico with Midjourney’s much-derided emphasis on gesture over accuracy, the emphasis Miele’s text clearly called for.

Even though Miele didn’t name “Rodin” or mention “sculpture,” there is an aesthetic connection distilled and rendered here in this contorted anatomy, grasping gestures, and embryonic imagery.

Unpleasant though some of these synthesized images may be, they are a real intersection of Miele’s sense of touch, his understanding of Rodin’s works, his interpretation, his text, and Midjourney’s statistically, algorithmically driven choice of relevant visual motifs. Like human artists before it, here now the AI itself has chosen from a pre-existing inventory of visual elements from its vast database of cultural references and recycled, repurposed, and adapted them to reflect Miele’s words in something new.

I think these images are the project’s most fascinating and promising results. They illustrate Artificial Intelligences’ ability to discover, exploit, and express deep, unexpected, semantic, emotional, and narrative connections between perception, language, and imagery.

VISIONS OF AN AI FUTURE

Our collaboration produced more than four thousand images, and each one raises more questions than it answers—as does the project itself. It’s not clear what comes next.

This technology is improving at an incredible pace. Improvements seem likely to proceed faster than we could possibly zero in on or identify any best-practices for whatever’s available at the moment. There appears to be a core functionality for visually communicating some kinds of meaning—whoever is authoring it, including blind people—with very strange potential. But it lacks precision and feedback mechanisms.

Midjourney has recently begun testing an image-to-text description tool that gives users written feedback on the content, mood, and style of images, as an aid for honing their prompt-writing skills. With some refinements, blind users could conceivably use it to receive quick, automated feedback on their own image generations with detailed descriptions of their subjects and compositions. This new capability may help blind users produce visual resources with some confidence that the results reflect their intent. It’s an obvious path for our continued exploration and experimentation, and with some attention from Midjourney’s developers on some use-cases they may not have anticipated, it could open up many possibilities for blind users.

When AI text-to-3D modeling systems soon become available, blind users may be able to use fine-grained haptic VR feedback devices or other tactile displays to physically inspect and interact with their digital creations by touch—or to 3D print them and hold real-world, tangible objects, whatever they may be or represent.

But there’s more on the way, and soon, and much of it seems to be visually driven. AI text-to-video is progressing rapidly, and researchers are using the underlying tech that powers Midjourney to resolve fMRI brain imaging into coherent images of subjects’ mental imagery. We may soon be able to record imagery from our dreams.

Miele has concerns about blind people being left out of visually oriented AI advancements: “When AI-assisted image generation is connected to biometrics and direct brain activity for emotive and cognitive inputs (instead of text), who's going to need spoken language anymore? Well... blind people will, as well as anyone who has any kind of visual processing neurodivergence. So the brave new world of AI image generation might be great for sighted people, but I'm a little nervous about what new communication barriers it may bring for blind people.”

I think of Miele’s concern as a counterpoint to a complaint about AI-generated imagery that echoes an outdated criticism of some abstract art, as well as any kind of computer-facilitated art: denying a work’s merit by questioning the artist’s skills or tools, specifically along the lines of “Anyone could do that.” In our context, that observation of course commends AI image synthesis tools, because that’s the point. With these tools, anyone can make images. That’s one of the reasons the technology is so radical, and so important. And to address Miele’s concern, that’s why we should keep exploring ways to make it true.

Cosmo Wenman is CEO of Concept Realizations. He can be contacted at twitter.com/CosmoWenman and cosmo.wenman@gmail.com

If you enjoyed this story, please share it and consider subscribing. I’ll be writing more about this project, including about the pop culture and creative writing-related images we created. I’ll also post occasional stories here about universal access technology and design, 3D scanning and replicating artwork, and, soon, important updates about my freedom of information lawsuit in Paris against musée Rodin, in which I’m seeking to establish public access to all French national museum’s 3D scans of public domain works.

ABOUT THE PROJECT AND ITS PARTICIPANTS

The project’s 4,110 image results and their complete text prompts and Midjourney parameters are accessible via conceptrealizations.com/ai-experiment-images-prompts.

The three participants who contributed texts for image synthesis and collaborated on the project design:

Brandon Biggs, CEO of XR Navigation, CFO at Sonja Biggs Educational Services Inc, Engineer at the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute. Biggs received his masters in Inclusive Design from the Ontario College of Art and Design University and is a PhD student in Human Centered Computing at the Georgia institute of Technology. He can be contacted by visiting brandonkeithbiggs.com

Joshua Miele, research scientist specializing in adaptive technology design, 2021 MacArthur Fellow, Distinguished Fellow of Disability, Accessibility, and Design at UC Berkeley's Othering and Belonging Institute, and Principal Accessibility Researcher at Amazon’s Lab126. Before joining Amazon, Miele conducted research on tactile graphics and auditory displays at the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute. He can be contacted at twitter.com/BerkeleyBlink

Lindsay Yazzolino, nonvisual designer with a background in cognitive neuroscience research and public transit accessibility; cognitive neuroscience researcher investigating how blindness shapes cognitive abilities such as Braille reading, language, and touch and sound perception. She is a user experience designer at CVS Health and is also a tactile technology specialist, collaborating with scientists, museums, and product developers to create multisensory, hand-catching art and experiences. She can be reached at lindsay3.14@gmail.com

The project was conceived and organized by Cosmo Wenman, CEO of Concept Realizations, a digital design and fabrication firm specializing in tactile and universal access exhibit design, artwork replication, and bronze foundry applications. Wenman is also an open access activist in the cultural heritage field. He can be contacted at twitter.com/CosmoWenman